A Tale of Two Fisherfolk: Entangled Stories of the Anthropocene

"What is it like to be a fisherfolk in Koshi Tappu?"

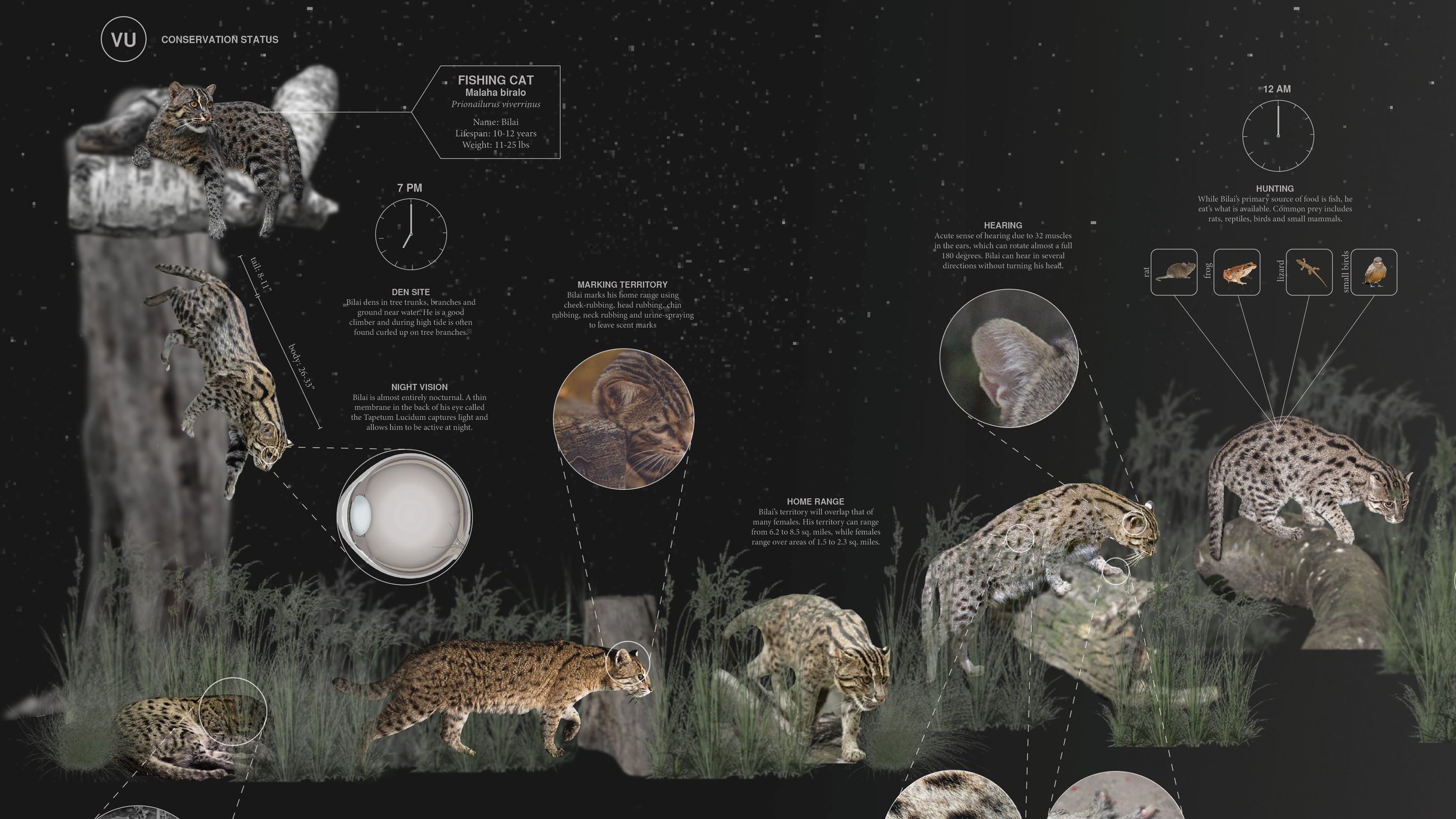

This question was my primary motivation for 4 months as I immersed myself in the lives of Bilai the Fishing Cat and Gulabi ji the fisherman in the wetlands of the Koshi Tappu, Nepal. I was challenged to consider the lives of non-humans and humans in conflict and how the built environment can act as a mediator between the two.

I began my exploration by conducting rigorous secondary research into both stakeholders and mapped out their entangled lives in the drawing below. The remainder of this exploration was spent on designing an “empathy portal” - a communal fishing grounds where the two fishing communities along with other wetland species learn to coexist and share this grounds.

This project was featured in the London Design Biennale Care Pavilion 2023

Timeline: 4 months. In partnership with KTK Belt and Priyanka Bista.

An interesting finding from the mapping above was the overlap at 3 am as a moment when the two fisherfolk meet to share stories and fish. Not only is there a mirroring of Bilai's nocturnal lifestyle and Gulabi ji's diurnal lifestyle, but there is also a rapid decline of fish in Koshi Tappu which has dire effects on both fishers.

Although this particular story is friendly between the two, it may not stay this way - in fact, many other fishermen are already in conflict with fishing cats on a daily basis.

Fish ponds are often cited as a place of conflict, attracting species such as Fishing Cats who come here in search of food, leading to competition and violence between the two.

To understand more about the problems faced by fisher communities, I delved deeper into the larger context. I discovered that the rapid decline in fish is a reflection of larger problems that endanger a multitude of wetland species. What I focused on is the problem of overfishing and poisoning of waterways with sewage and pesticides seeping in from farmlands. This has led to eutrophication and the growth of invasive species such as water hyacinth - the primary cause of the decline of fish in Koshi Tappu.

With natural wetlands being destroyed, Fishing Cats are forced to enter the man-made fish ponds (as we saw with Bilai) and are now increasingly dependent on them.

Fish ponds emerged in Koshi in the 1990s as fish hatcheries, a source of income for fishermen. Many were converted from previous healthy wetlands. Today, these are sites of conflicts between human and non-human species, and it has increased extractive fishing practices. The problems that fisherfolk are experiencing emanate from the issues of wetland destruction and are a result of an extractivist attitude. There is a sense of urgency to create new ways of coexistence.

How do we change this extractive narrative - one of competition and conflict - to one of sharing resources?

Out of this question emerged an empathy portal - a communal fishing ground focused on restoration and sharing of resources.

The site I selected exists at the interface between the reserve (to the west) and the settlement (to the east). I chose this site because it echoes the problems of other former wetland sites around the river's edges.

Due to the rapid, uncontrolled growth of water hyacinth, this habitat is in dire need of restoration.

My intervention will focus on the southern end of the site. I honed in on the specific problems that need to be solved in order to create a communal restorative fishing grounds. This would be a long-term plan that I laid out in this diagram.

To reuse water hyacinth I proposed a new typology: Floating wetlands, made of water hyacinth floats overlaid with local matter such as bamboo, wood, dung and dirt. These help to 1) filter the water pollution while also providing habitation and food for birds and insects and 2) can be used for garden beds. This is already an innovation seen in Inle Lake, Myanmar where farmers use water hyacinth floating gardens to grow crops and reduce dependencies on fish.

The hope is that 1-2 years from now we’d see a decrease in the water pollution on site, which would promote the revival of fish.

To help maintain a healthy aquatic ecosystem - I introduced another typology: a fish-pen system. Wooden frames are erected in the soil bed to create enclosures for aquatic species. The fish feed off of the algae and plants within the fish pens. A precedent I was inspired by is a self-sustaining fish pen system in Ganvie, Benin. This is a local aquaculture system that focuses on protecting the water's productive capacity and ecosystem.

What is created here (floating wetlands and aquaculture system) can be replicated across Koshi Tappu, which is why I thought about this as a “kit of parts” for fishing grounds.

Considering multiple interventions is necessary if we want to revitalize this wetland, from removing and reusing the water hyacinth to reducing the water pollution levels, in order to support fish and fishing communities.

In the form of an experiential section drawing (below) I captured a scenario 3 years from now. It shows an alternative reality of the two fishing communities coexisting and sharing this fishing ground - one community at night (Bilai/Fishing Cats) and the other (Gulabi ji/Fisherpeople) during the day. Although Fishing Cats and fishermen would never physically meet, we see their interactions through their markings - leftover fish, foot/pawprints, markings on trees and scat.

During the day this space is not just for fishermen to fish together, they also test out new fishing techniques, how to make organic nets, and learn how to care for wetland species and habitats. They test the water quality, and monitor the different habitats- ensuring all fishing communities - birds, crocodiles, fishing cats are thriving. Other members of the community (not just fishermen) are also involved - farmers take the water hyacinth to turn into organic fertilizers and look after floating gardens while weavers sit around weaving, chit chatting and learning.

Through this drawing we see how the fishing ground becomes a living transcript through which the two and other wetland species leave tracks sharing stories about their daily lives.

This space is about the collective. And collectively the multispecies communities are working together to make this space a thriving wetland like it once was, setting the precedent for revitalization across Koshi Tappu.

The hope is that new fisher communities hearing about the fishing grounds and the stories of fishermen and fishing cats will come to experience the thriving wetland communities that inhabit this landscape. And when they leave, they will take these ideas back to their own communities and we would see the ripple effects with new communal fishing grounds emerging across the Koshi landscape.

Grounded on rewriting extractive relationships, and rebuilding new ways of engaging.

My work displayed at the London Biennale Care Pavilion 2023